Walltown University: Christ & Culture 101

/One of the most recognizable voices of television history is the voice of Charlie Brown’s teacher Mrs. Donovan. It only takes a few seconds of listening to her voice for your mind and body to be jolted back into those hard, plastic chairs that filled your middle school classrooms. Like Charlie Brown, we have all suffered through classes where the content seemed incomprehensible to us. For me, this feeling was the result of the disconnect between what I valued as a kid and what the education system told me was important. This dilemma is not limited to schools. This feeling of disconnect can also be experienced in other social settings like churches. For young people, youth pastors can often come across like Mrs. Donovan. What the leader might consider to be an important lesson can actually be irrelevant for the students. I learned this lesson the hard way while facilitating Urban Hope’s bi-weekly bible study called Bible Jump Off.

During my first year at Duke Divinity School, I learned incredible information about the bible, and I tried to pass this knowledge to the students I served. However, I often failed to effectively share this information with them. Although my initial lessons were creative, it was apparent that I had not connected the lesson with the student’s lives in an impactful and meaningful way. Where did I go wrong?

Alongside Urban Hope’s Leadership Team, I found the answer to this question in Christopher Edmin’s book, For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood . . . and the Rest of Y’all Too. In his book, Edmin points out that a student’s context and culture are not barriers that a teacher must overcome. Instead, culture is an indispensable tool that must be utilized. There are three steps that a teacher must take to develop a relevant and meaningful lesson plan. “The first involves being in the same social spaces with the neoindigenous [those who are native to the urban context], the second is engaging with the content, and the third is making connections between the out-of-school context and classroom teaching” (Emdin 140). Edmin makes it clear that a student’s context and culture is what primarily matters to the student; therefore, the responsibility of a teacher (pastor) is not to persuade the student to abandon his or her culture in order to understand and accept the foreign culture of church. Instead, a pastor is responsible for demonstrating that a student’s culture can be cherished and embodied by the teachings and practices of the church. Edmin’s wisdom became an important guide for me to follow as I developed lesson plans during the season of Lent.

Two weeks after the murder of Stephon Clark, an unarmed black man shot by Sacramento police, Christians around the world proclaimed that “Christ is risen.” Yet, facing the wake of Stephon’s death, this belief felt like a mirage. Christ had come to set the captives free, yet Stephon’s life was bound to an unjust world and legal system (Luke 4:18). How could I communicate the reality, relevancy, and potency of Christ’s resurrection to students who live in a world in which black people are still held captive? Considering Edmin’s advice, I began developing a bible study that primarily engaged the student’s culture.

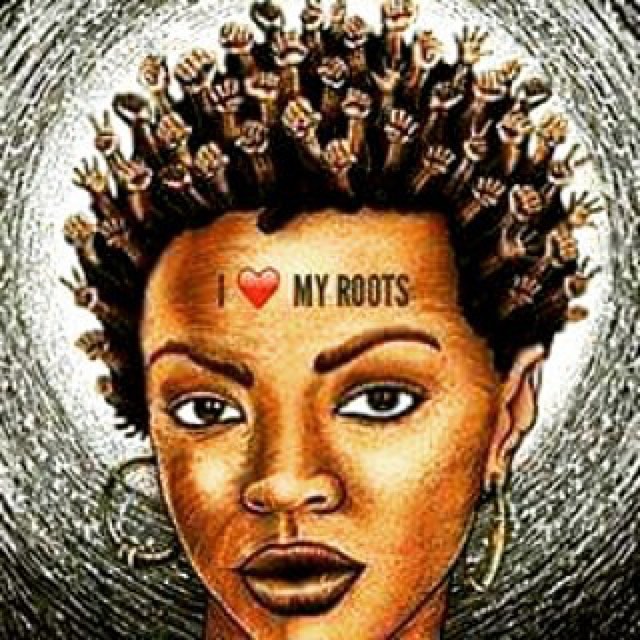

First, the students and I examined the artwork seen below.

Artwork displayed on t-shirt sold by Dareaccessories on Etsy

For us, this piece of art illustrated the innate, sacred worth of black bodies and black culture. And it restored our inner-well of black self-love.

Once we had established the beauty of black life, the students and I examined Kendrick Lamar’s song “Pray for Me.” This song vocalized the despair, pain, and sense of isolation that we all felt after hearing the news of Stephon’s death.

“Tell me who’s gon’ save me from this hell

Without you, I’m all alone

Who gon’ pray for me?

Take my pain for me?

Save my soul for me?

’Cause I’m alone, you see . . .

I fight the world, I fight you, I fight myself

I fight God, just tell me how many burdens left

I fight pain and hurricanes, today I wept

I’m tryna fight back tears, flood on my doorsteps Life a livin’ hell, puddles of blood in the streets Shooters on top of the building, government aid ain’t relief

Earthquake, the body drop, the ground breaks

The poor run with smoke lungs and Scarface

Who need a hero? (hero)”

“Who need a hero?” The resounding answer to this rhetorical question is “us.” We desperately needed a hero, but as the police officers opened fire on Stephon Clark, God did not intervene. God was not there.

However, this was not the only time that God had abandoned one of his innocent sons. Recall the events of Good Friday, as Jesus hung on the cross, he cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). The Son of God had been abandoned and humiliated in front of the world. Jesus, an innocent man, died at the hands of the Roman police force. As Jesus experienced the tragedy of his life, he was nearly left speechless. Instead of crying out in confidence that God would rescue him, Jesus vocalized the pain of abandonment. In doing so, Jesus allows the black community to also cry out in pain.

Jesus’ cry on the cross drew upon the words of Psalm 22. Like Kendrick’s song “Pray for Me,” Psalm 22 similarly creates a space where truth can be boldly announced.

“1 My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are you so far from saving me,

so far from my cries of anguish?

2 My God, I cry out by day,

but you do not answer,

by night, but I find no rest

6 But I am a worm and not a man,

scorned by everyone,

despised by the people.

7 All who see me mock me;

they hurl insults, shaking their heads.

9 Yet it was you who took me from the womb;

you kept me safe on my mother’s breast.

10 On you I was cast from my birth,

and since my mother bore me you have been my God.

11 Do not be far from me,

for trouble is near and there is no one to help.

12 Many bulls surround me;

strong bulls of Bashan encircle me.

13 Roaring lions that tear their prey

open their mouths wide against me.

14 I am poured out like water,

and all my bones are out of joint.

My heart has turned to wax;

it has melted within me.””

Before this lesson, neither I nor the students would have considered turning to Psalm 22 to process the loss of Stephon Clark. Yet, when read alongside Kendrick Lamar’s song “Pray for Me,” Psalm 22 became a powerful way of welcoming God into our space of mourning and despair. By taking our culture seriously, we opened up space for God to speak into our lives. Experiencing spiritual insight inside of black culture is exactly what Chris Emdin’s work envisions. For him, and hopefully for us, we can begin to realize that culture is a vital tool that must be understood and treasured in order to communicate that God is relevant to our lives. As we, the Church, continue to "make disciples of all nations," what are the cultural contexts of our physical and spiritual neighbors that we must consider, listen to, and treasure, in hope of having the nature of God revealed to ourselves and others?

-Xavier Adams is from Kansas City, KS, and just completed his first year at Duke Divinity School. He is pursuing a Masters of Divinity with the hope of working with youth either in a church, non-profit or classroom setting. During the 2017-2018 academic year, he led our bi-weekly youth bible study called Bible Jump Off. This summer, he is sticking around to serve as a camp counselor in the 2018 Urban Hope Summer Camp.